Sunday, October 4th, 2015

written by Tim Hansen

If one wants to gain an insight into a composer’s brain, reading their bio is a good place to start. Usually these are carefully curated mini-autobiographies, where the composer outlines what they consider to be their proudest achievements, most cherished influences, beloved mentors and general philosophy on music and the universe in general. Devoid of word limits or the harsh eye of an editor, a composer’s bio can easily turn into a florid treatise on the nature of contemporary music several pages long, or else a bland, endless shopping list of universities, festivals, collaborators and awards described with the readability of the ingredients on a packet of rice crackers (a crime of which this writer is definitely guilty).

Consider then, 2014 JFund awardee Jascha Narveson’s bio on his webpage, reproduced here in its entirety:

“Jascha Narveson was raised in a concert hall and put to sleep as a child with an old vinyl copy of the Bell Laboratories mainframe computer singing “Bicycle Built for Two.” He now makes music for people, machines, and interesting combinations of people and machines.”

Talking to Narveson, one gets the impression that the Canadian-born New Yorker is unusually unsentimental about his vocation or his art. That he is passionate about music, there is no debate, and his list of achievements is eyebrow-raising (even if one has to go hunting the internet for them), but Narveson exudes a friendly, humble pragmatism about his work that is refreshing.

“I’ve always been passionate about listening to a wide variety of music, and I guess that at some point I just wanted to start adding to the conversation,” Narveson shrugs. “I also like the activity itself: sitting idly and thinking about music at my own pace, focussing in on details or zooming out to think about larger ideas… I love performing, but the way I think about music is better suited to being able to take the time to shape things the way I hear and feel them.”

As a child, Narveson grew up in a household that would be considered strikingly musical by even the most seasoned veterans. “My parents ran (and still run) a very active chamber music house-concert series in my hometown of Waterloo, Ontario,” explains Narveson. “They’re up to over 70 concerts a year by this point, and it’s one of the busiest programs in the country. My childhood was regularly punctuated by artists from all over the world showing up to rehearse and play concerts there, and many dinners were spent listening to the piano tuner working upstairs. My dad’s record collection takes up entire walls of their house – classical music literally surrounded me 24 hours a day.”

Despite growing up in this musical maelstrom Narveson is, by his own admission, “surprisingly unskilled as a musician”. Instead his approach to composition is driven partly by the joy of self-reflection and partly by revelling in the simple act of creation, a sort of benevolent “mad scientist” who loves to mix music and technology together to see what happens. His creations are, in a word, unique, from stand-alone works for electric guitar quartet Dither or his ongoing, ever-evolving collaboration with other Princeton alumni in Sideband. Despite this electronic adventuring, it’s all in a day’s work for Narveson, and he describes his use of technology in his characteristically unassuming way.

“Composers have always used whatever was available, and there’s nothing special about using technology any more,” he says. “I use technology because I have an affinity for it, so the choice of tools per se doesn’t connote anything, to me – it’s the things expressed that are worth considering.”

The “things expressed” in this case – his JFund piece – came from a controversially topical source: Wall Street. Specifically, the “flash crash” of May 6, 2010, in which trillions of dollars were wiped from the stock market before bouncing back to almost the exact same level in a matter of about half an hour (undoubtedly leading to more than a few stockbrokers needing to go have a lie down afterwards). It later emerged that this happened due to the industry’s growing dependence upon little computer algorithms called “bots” that, in a histrionic nutshell, went rogue and blew up in their masters’ faces. (I’m not even going to pretend to understand it but the events are described here if you’re curious). On the back of the GFC of 2007-2008, the world was understandably jumpy, and a great deal of post-mortem analysis went into understanding exactly what happened.

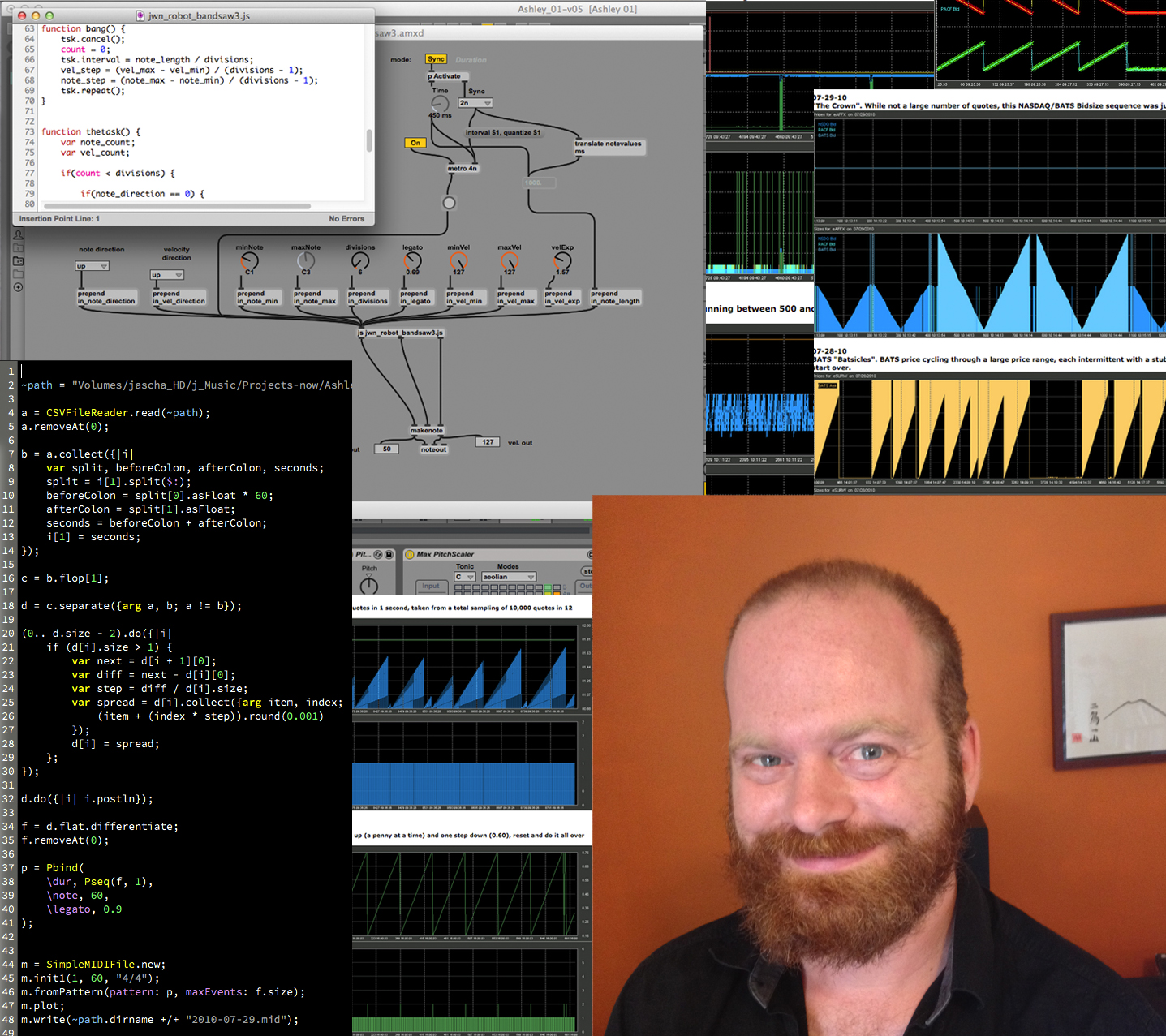

Narveson happened upon an article outlining the crash, and was struck by the “whimsical, evocative” names given to these so-called “algorithmic crop-circles”, like “Ask Mountain,” “Knife” and “Bandsaw”. But it was the gallery of data visualizations of the quirkily-named algorithms accompanying the article that really began to spark Narveson’s imagination.

“The shapes were intriguing, and seemed innately musical,” says Narveson. “The social context was fascinating, painting a picture of a global economy that’s increasingly controlled by the complex interaction of automated systems we don’t understand, quite possibly at the service of an ever-richer techno-elite who are kind of robbing us blind.”

From this seed, Narveson’s JFund piece – provisionally named Flash Crash – grew. Composed for solo cello and electronics (and performed by cello virtuoso and new music champion Ashley Bathgate), the piece will use the same technology that caused such a ruckus back in May 2010 to create the work through live processing as Bathgate plays.

“High-frequency trading on the market is accomplished by algorithms that search for tiny price discrepancies and exploit them thousands of times per second,” explains Narveson. “These are informally called robots (or, more casually, ‘bots), in much the same way that we use the term to describe the Twitter and Facebook users who are obviously computer programs meant to sell us stuff and/or steal our personal information. These bots scour the markets and just do their thing mindlessly, so my own “bots” will scour the input from the cello and react to it in a similarly automated way.”

From this writer’s perspective, Narveson is clearly a pioneer, but, as has already been intimated, he doesn’t see it that way. To him, there is nothing more natural than combining technology and music, though if others don’t want to go down that path, then that’s fine too. “These days, I get the feeling that composers are less worried about being new, and are happy simply to make new music using whatever means are interesting to them.”