JFund Profile by Michael Cyrs

“Genre-defying” and “experimental” are words that critics enjoy tossing around, especially when it comes to genre-mixing. However, in music, most genre-mixing is old news, and the terms only gesture at describing a diverse arrangement. Every once in awhile, though, someone earns the terms. M. Lamar’s records are shining examples that successfully blend opera, doom metal, classical, and electronic music, usually within the course of one song. Sound confusing? Give him a listen and you’ll see what I mean.

Lamar had just returned to Brooklyn from playing two shows in Salem, MA, and I laugh at the appropriate combination: his appearance, from upside-down cross jewelry, various tonsure, and black cloaks of numerous lengths, isn’t limited to his press photos. “This is what I look like all the time, but in Salem, there are many others on the street with a similar aesthetic.” Lamar looks exactly like his art, and it’s obvious that his appearance isn’t merely a front.

He says he’s always been a genre polyglot. During his time in college, he sang in a rock band, but quickly became sick of the subservience to rhythm and lead guitar. “I didn’t have time for that,” he says. The follow-up to his answer is a long list of influences: Cecil Taylor, Marilyn Manson, and avant-garde soprano Diamanda Galás are mentioned.

Lamar takes these influences and mediums and creates the conditions through which historical contexts can appear. On 2015’s “In The Belly of the Ship,” Lamar sings poetry depicting human beings living next to human waste on slave ships. The piece, like most of his work, is lengthy and immersive, and Lamar acts as more of an enlightened historian than anything self-serving: “Right now I’m having difficulty with having a body-ness,” he explains about his performances. “The thing about music and sound is that it’s kind of existing in a transparent place. I’m really deeply invested in transcendence.”

As such, Lamar wants to make something beyond a particular moment. At first listen, it seems his longform structures were intended to preserve the present moment. In truth, Lamar seeks to go beyond his body, which “only gets around 80-90 years anyway.” His use of aging musical forms like European classical and avant-garde are further proof that he’s less interested with the here and now than comparable modern artists like Swans or Darkthrone. Whether he spends 20 seconds holding a high note or a primal growl, he’s moving beyond the world’s physical forms, not embracing them.

Give this year’s Funeral Doom Spiritual a listen, and you’ll see the various shapes Lamar’s ideology takes. On the record, he worked closely with another musician who hardly conforms to the norms of his given genre: American black metal artist Hunter Hunt Hendrix. In 2010, Hendrix wrote an essay titled Transcendental Black Metal that upset the philosophy of the Norwegian art form. He replaced rhythmic terminology such as the blast beat, a common trope among black metal, with his own “burst beat,” and the difference was difficult to comprehend. The metal community was by and large outraged at this uppity artist’s affirmations, but Hendrix’s music with his band Liturgy was so excellent that many of his detractors were silenced.

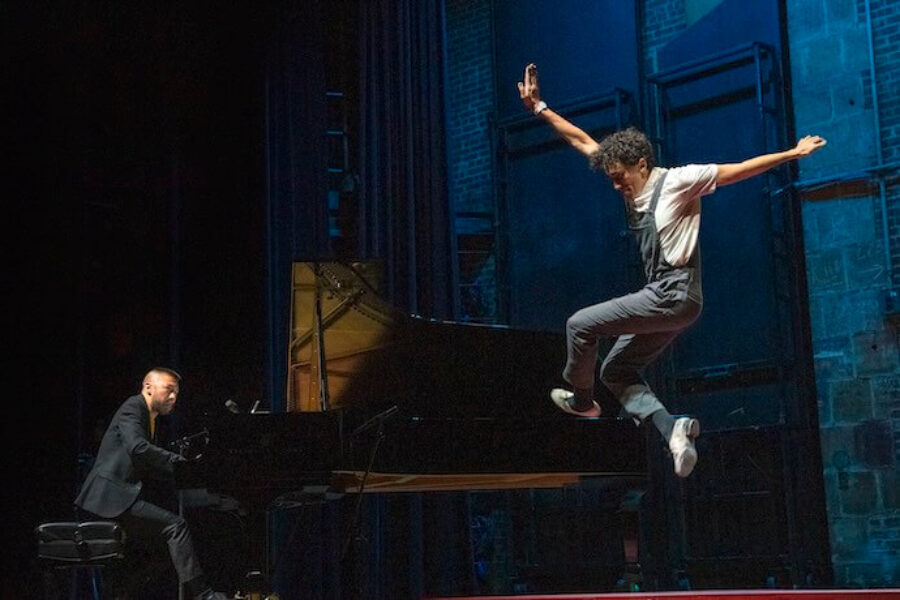

Lamar and Hendrix are a match made in heaven. “It was sort of like a band jamming,” Lamar says. “I would perform my pieces and he would jam along.” The results on Funeral Doom Spiritual are gorgeous. Chaotic swirls of avant-garde piano approach infinity on “They Took You From Me,” and bursts of electronic noise and syncopated rhythms flit in and out of the frame. Lamar sings few lyrics although he spends most of the track’s length holding a note in his strong tenor. The rest of the record is similarly timeless, occupying a space between African-American folk tradition, ambient, and the preservation of classical music through mediums that few others can successfully tame.

It’s the folk tradition in particular that Lamar strives to become part of, though the definition for “folk”–like other genre terms–is anything but cut-and-dry. 2017 is a time where it could be anything from a frat boy with an acoustic guitar to an indie rock band with an accordion. The term belongs to no one, and that folk music was originally something carried on through tradition instead of recorded work. These are the ideas that Lamar, apart from his strict vocal and piano practice, labors over unceasingly. He hopes to represent something unburdened by time, and the void of sounds he creates accomplish just this. Funeral Doom Spiritual revels in what Lamar describes as a “bodylessness” where he becomes a vessel for African-American history, goth-tinged expressionism, and the sound of a devil’s dance at midnight. “If I can become part of that folk tradition, I’d be thrilled,” he says.

Next up on the docket for Lamar is as varied as what’s behind him. In a move away from performance, he’s composing vocal pieces for all black opera singers. Calling the project The Lynching Suite, Lamar seems simultaneously eager and puzzled about not performing the music himself. For once, he’ll no longer be the vessel for an experience, but the composer behind the scenes. This is hardly his only current project, and it’s comforting to know that Lamar’s talents are matched with a tireless work ethic. Though his works paint a frightening image at first, light peeks in through the cracks if you give them the attention they deserve. Until the day where Lamar’s work gets a specific genre tag, we’ll be scratching our heads trying to explain it, and revelling in its abstract wonder.

Photo by Alex Norelli.

Related Posts

Anatomy of a Commission: Rethinking Composer-Ensemble Commissions from a Visual Artist Perspective