Written by Michael Cyrs

Even if it’s with someone unquestionably genuine, verbal communication is difficult to recall. Although one may remember the words that were spoken, there were feelings, objects, weather, and countless other subatomic details that were simultaneously present during conversation. The same goes for life events. Say you lost a job or fell in love. How can that deeply personal experience be translated without filter?

It was these underlying details that my mind’s eye pictured the first time I listened to Aleksandr (Alex) Brusentsev’s “Small Victories” for violin and piano. A three-part piece, the music flits between block chords in the bass and arpeggios in the treble that begin in unison, but fall in and out of rhythm as the piece goes on. When I listen, I imagine the neutrons and protons of the manuscript coming together as Alex notates. This isn’t the experience he was directly trying to relate when composing the piece, but it’s a start. The physical realm was intact enough for composition to occur, at the very least.

When I sat down with Alex in a South Minneapolis coffee shop, he was interested in my reaction. Sure, it wasn’t exactly what he’d pictured, but it was my own interpretation, and that’s what he seeks out more than anything else. “I feel like the best thing I can do is be as me as I can be, and to encourage others of the same thing.” His are pieces that are deeply emotional, and if anyone can have a positive reaction, that’s a beautiful thing. If someone doesn’t connect, at least they’re able to say so. “Not everyone’s gonna like what you’re doing. Not everyone’s gonna get along, and that’s genuine.”

How did this happen? Why avant garde as the medium for Brusentsev’s expressions? “It was a conscious decision,” he explains. “My plan in college was, totally, to become a full time guitarist.” After tendonitis and carpal tunnel forced Alex to take a break from guitar, he took composition lessons and decided they would be his main focus. “My love of music predates my memory. I’ve heard stories of me playing the piano and singing as a kid, but I have no recollection of them.” We’re able to talk about how pop music, despite its amazing abilities, can sometimes take a backseat to classical, jazz, metal, and, in Alex’s case, avant garde. His journey into this format is in line with his compositional ethos. That is, it’s an honest one.

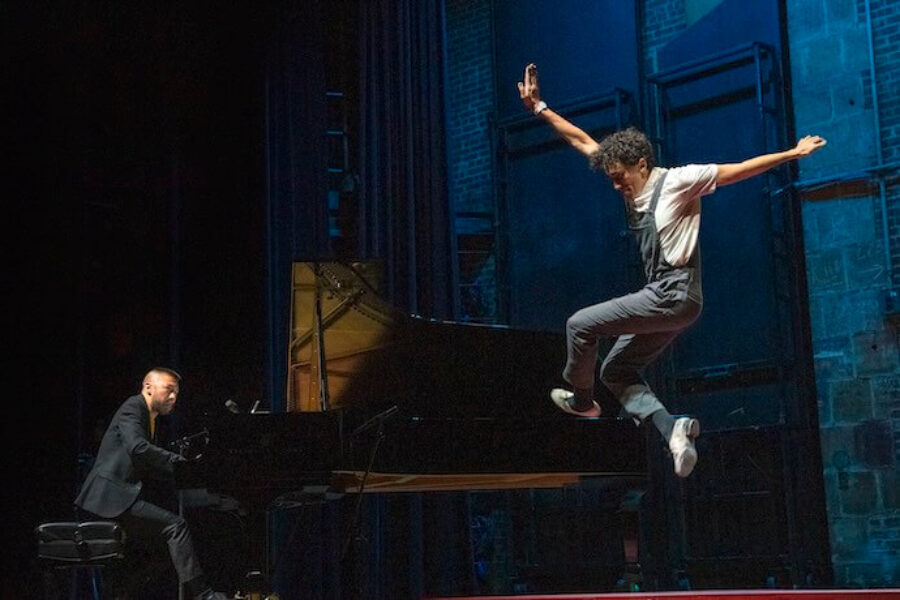

A beautiful snapshot of Alex’s work can be found in his series Connect The Dots. Here are four solo pieces and performers that were granted a stage to perform one Brusentsev piece, and another of the performer’s choosing. I was most moved by the violin piece. To me, the spastic use of extended techniques evokes a dream sequence from which violinist Tanya Sweiry wakes from in the middle of the piece. Reality comes flooding back, but spots of odd notes and syncopation remind Sweiry that the dream has only recently ended.

In the improvisation, Sweiry is able to drone two violin strings while holding a third dormant in the middle. By bowing high on the neck, she then dramatically brings the third string into the chord. The results are gorgeous. I asked Alex how he was able to notate this technique, and it apparently happens more with one on one communication with his performers as opposed to a “here’s what’s written, now play it” mentality.

This is an important element of Alex’s method. He sows the seeds of his ideas in verbal and written communication before performance is even mentioned. Each of his manuscripts comes with a short paragraph with notes for the performer. They aren’t direct instructions, but are platforms from which honest collaboration can begin. Just as understanding someone’s upbringing can help you communicate with them, understanding the basic emotions behind a composition can help you learn to play it. As Alex explained to me the feeling he got when Sweiry was able to accomplish the drone technique, it became even more evident that he has a clear appreciation and reverence towards collaboration.

Alex does the same thing for the listener by writing a separate paragraph that’s available before performances and in the manuscripts. “In music, when I get something right, I have said what I have to say in the best way that I’m aware of. Then I can do what I can do to make that thing more accessible by describing it in words.” A unique take on the composer/audience relationship, Alex hopes to tell the basic story of the piece as one would their life story. Before genuine connections can be felt, a base level of understanding is necessary.

The reason Alex does these things for performer and audience is a wise one. Although many of his compositions are deeply emotional, personal versions of life events, he understands the pretensions behind the assumption that it’s all about him. In other words, he’s humble: “On one hand, it’s deeply personal. But I wouldn’t go through the trouble of writing it down, getting someone to play it, and getting someone to listen to it if I didn’t think it had value.” There’s value in his own experiences and feelings, but they are moot without another perspective. Even if the listener doesn’t know exactly what events are being represented along the waveforms, they can still respond as passionately as I did to Sweiry’s performance. “For me, there is a story. It’s fairly concrete, but not necessarily linear. I have no intention of communicating that concrete story to anyone. I’m interested in one level up: not the facts, but the feelings surrounding the facts.”

Since the concrete details and the broad strokes of the pieces are represented, it follows that Alex would include a visual element as well as a musical one. As he explains, written music, in essence, is a bunch of dots on a page. Alex uses that shape to provide a picture of the music. As evidenced by his lovely website, these dots can be viewed from all four angles, just as a piece of music can be observed from different perspectives and points of view. In particular, the manuscript cover of Between the White and Yellow Lines shows the exact mental image I pictured when listening to the piece. It’s incredible that a mind so capable of constructing moving music is similarly capable of visually representing it. This combination of talents is hardly common.

“If my music had a slogan, it would simply say ‘try looking at it from here.’” This summarizes Alex’s appreciation for perspective and humanity. He tries to convey his own story, yes, but simultaneously recognizes his audience’s ability to have their own reactions. Even though I didn’t know what life event triggered a piece like “Small Victories”, I still felt a physical and emotional setting in which such an event could take place. In essence, I could hear a passion both expressive and sophisticated. Fortunately, I’m not the only one who feels this way, and Alex is currently spearheading another Connect the Dots series. If talk is indeed cheap, we still have Alex to paint a more detailed image of storytelling and human connection.

Related Posts

Anatomy of a Commission: Rethinking Composer-Ensemble Commissions from a Visual Artist Perspective