written by Michael J. Cyrs

In 1845, when expressionism was decades away from being an identifiable movement, artist JMW Turner showcased four oil paintings at London’s Royal Academy. Despite the poor reviews, his use of broad strokes to evoke natural light was novel for its time. There’s a pervading suggestion that Herman Melville took these paintings as an influence for his whaling epic Moby Dick, which was published soon after. Both artists used abstract techniques to tell stories, and Melville could easily have taken cues from Turner’s marine exhibitions while in London. By 1851, the year Moby Dick was published, Turner had passed away. But his images of a majestic sea continue to live on to this day.

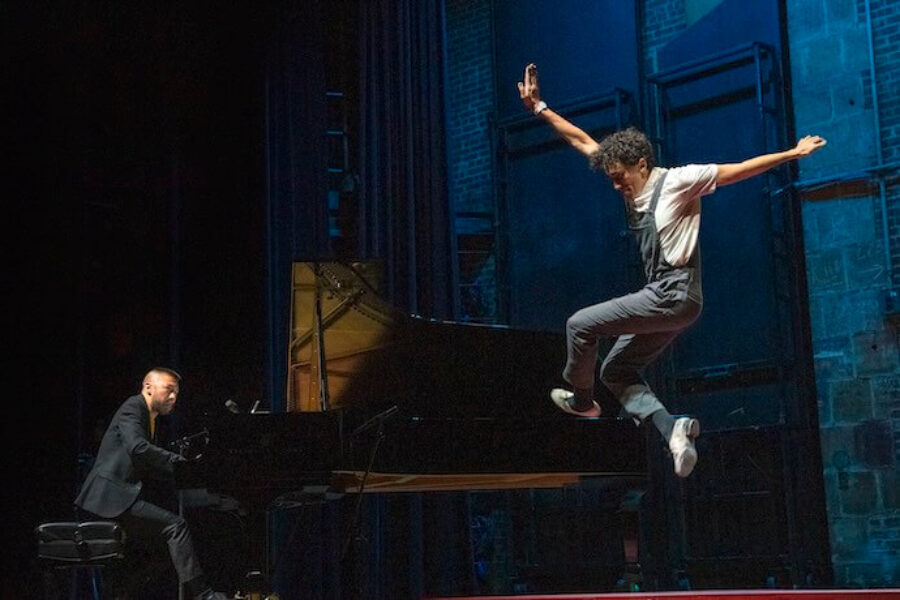

New York-based composer and 2016 Jerome Fund awardee Brian Petuch is a descendant of Turner’s and Melville’s, albeit in a different artistic medium. Throughout the 11 minutes of his recent work “The Pequod,” the music is peaceful, violent, and transcendent. “It’s loosely based on Moby Dick which is easily the best book I’ve ever read. It’s existential and odd, not just a plot from beginning to end,” he explains. Petuch’s piece starts as a post rock string drone, but things turn dark at the three-minute mark. Harsh electronic waveforms dominate the EQ spectrum. You can feel the tension in the air before the legendary whale finally surfaces, which is precisely what happens in the next section. The electronics stiffen and take on a physical form. The strings, like the sea around the boat, adapt quickly to the massive lifeform around them.

“The piece has a giant conflict, and then it releases. But it’s not a happy release. The whole thing is an allegory for a lot of things.” Indeed, “The Pequod” sounds not only like a whaling ship’s journey under a scrutinous captain, but like an image of life itself. The strings represent the innocent beauty of childhood before the drama of adult life seeks to overtake that beauty. Towards the end, a peaceful agreement is made within the arrangement, and you’ll find contentedness that reflects old age.

What’s described here is merely the first version of “The Pequod.” Different musicians have become attracted to the piece, and Petuch has been asked to change it multiple times. But how does one go about re-arranging something so complete? “I don’t think of it academically,” he explains. “At the end of the day, it’s always a push and pull between impulse and thinking… There’s technical things you need to consider, but you have to contextualize them so much.”

Petuch’s words here are a snapshot of the broader implications of classical composition. Musicians don’t simply learn by rote and repetition. They have to take a step back from the theory and consider how the notes work toward a narrative. You can spend a lifetime making sure your piece is as mathematically sound as can be, but the ear is the ultimate judge.

Take the harp for example. Petuch was asked to include it in one of the subsequent versions of “The Pequod,” but couldn’t use the same process as he did with strings. “The harp can be this magically delicate, ethereal instrument. But you can also get a sound where you get all the low strings to buzz violently just like the sea!” Utilizing these extended techniques allows for more basic human impulses to take the place of the electronic buzz. There’s beauty in the linear setup of a harp, but there’s also a visceral component to utilizing its heavy wooden base as its own drum. “The Pequod” accomplishes the difficult task of appearing dainty, but was actually composed with very simple motives. “Elegance be damned at certain points!” says Petuch, laughing.

Although he currently operates in a fine art medium, his undergraduate history wouldn’t suggest as much. A student of commercial music at Florida Atlantic University, he learned all manner of digital workstation techniques but little in terms of music theory. To supplement his education, Petuch played bass in punk bands and learned to play with more raw intention. This method informs how he composes to this day not only when juxtaposing the beautiful with the garish, but on a compositional level as well.

Petuch flips between ugliness and beauty early in the composition process. “I moved away from delicateness [for ‘The Pequod’], but in ‘24 Hours’ I’m sort of going back to it,” he explains about his current work in progress. Due for premiere in April, “24 Hours” is broken into 24 parts for each hour of the day. Vignettes from Petuch’s earlier career make appearances as one of the hours. “I put small fragments off to the side, and then later I’m able to revisit these things like meeting an old friend.” However, revisiting an old friend isn’t always pleasant. “24 Hours” reflects this possibility. Be they single-chord repetitions for 30 seconds or complex sextets playing for 2 and a half minutes, the players are allowed to mix up the formula as they wish. “They could play them out of order and just follow their impulse if they like.” With such flexibility, it’s no wonder Petuch is able to orchestrate ideas as grand as Moby Dick and a Dali-esque image of time’s passage.

Like Turner’s maritime images, Petuch’s art likely wouldn’t have been appreciated for its full weight in the mid-19th century. Be they nonlinear plots, broad brushstrokes, or mixing strings with harsh electronics, these are abstract and unconventional methods. Petuch makes this idiom work by attaching recognizable themes like the passage of time or a famous whale. “8p is like one chord and they can play it as long as they want.” Naturally, you won’t hear the notes and immediately think of early evening. However, we can meditate on the piece and make those connections ourselves. What exactly does this piece represent? We’ll let our ears tell us.

Related Posts

Anatomy of a Commission: Rethinking Composer-Ensemble Commissions from a Visual Artist Perspective